–  Superior knowledge on the product being competed.

–  An engineering organization with up-to-date skills and talented experts current in their subject matter.

–  A “going concern†production program generating cash.

–  Infrastructure, facilities, labs, etc., needed for the new program.

–  Customer intimacy and mission understanding.

However, relative to the other competitors (i.e., challengers), incumbents are also burdened with impediments that are often barriers to winning. Paradoxically, many result from the above-mentioned strengths. First, incumbents are “on defense†stemming from their actions to protect and extend their current program.  Secondly, incumbents are burdened by elements of their last success as they craft their product offering in response to the RFP.

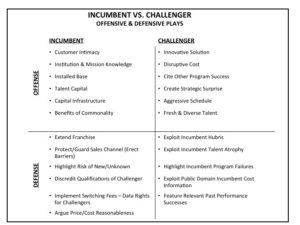

Impediments further manifest in traps that limit the incumbent’s actions and efforts in addressing the issues that matter in positioning for and winning a competition. In the context of winning, the contrasting (challenger versus incumbent) positions on important issues are presented in this Winning Insights post. These positions were derived based on more than 600 consulting engagements on winning, where TMI worked with either challengers or incumbents. We present a summary of offensive and defensive plays employed by both incumbents and challengers in the table below, followed by a discussion contrasting their responses on positioning to win and proposal offering issues.

Positioning to Win Positions

Focus. In competitions, the challenger focuses on winning while the incumbent’s focus (for too long) is on protecting the existing program, and the contest becomes the past versus the future. Hence, the incumbent is in the protection trap at the expense of positioning to win.

Collaboration to Help Customer Validate New Start. The challenger embraces and embellishes the new requirement and helps validate it with mission analysis and demos. The incumbent puts effort, although late, into product improvements, claiming adequate proven capability and low risk. Thus, the incumbent is burdened with the good enough trap that doesn’t address the new needs of the evolving customer set.

Also, the challenger is able to contribute more objectively to the customer’s affordability goal determination. Meanwhile, the incumbent views the government’s new affordability goal through the lens of the incumbent’s most recent development problems and cost growth. Hence, the incumbent is caught in its own reality trap. This creates the condition where the customer and challengers are optimistically pushing the new start while incumbent is perceived as resisting it.

Estimate of Pwin. The challenger concludes its Pwin is lower because it is the underdog. The incumbent’s Pwin estimate is higher because of their “going concern†strengths with attendant arrogance. The incumbent is burdened with the hubris trap and often puts too little effort into determining how to counter the challenger’s win strategy.

Commitment to Win. The challenger’s commitment to the new start is evident early and is consistent. The incumbent is ambivalent until too late. This results from being burdened by the denial trap with respect to whether the new start will really happen.

Management Alignment. The challenger’s leadership aligns around winning early. Meanwhile, the incumbent’s leadership is conflicted over protecting and extending the existing program versus fully embracing and committing to winning the new start. For the incumbent, future is the enemy of the present.

Staffing the Team. The challenger often selects the best talent from across the enterprise and brings in outside subject matter expertise on the “why†and the “essence†of the acquisition. Unfortunately, the incumbent, when realizing that the competitive acquisition program is really going to happen, selects people from the program organization to lead the effort. Thus, the incumbent starts with the existing team that it believes is the industry’s best. The team resists new talent and ideas and often ignores or rejects the broader innovative trade space needed to win. Tired blood becomes the trap.

Investing in Technical Advances to Win. The challenger illustrates the benefits of technology advances as the disruptive enabler for winning. The incumbent attempts to discredit the advance as not really necessary for the mission or too risky and will cost more. The incumbent resists moving out of its comfort zone trap.

The Integrated Product Offer

Performance Confidence. The challenger features its prior successes. And, it will use the incumbent’s recognized contract performance problems and the new program’s anticipated management challenges to drive acceptance of its technical and management response. This results in higher confidence for an executable program that is enabled by the challenger’s offer of design margins, schedule margins, and affordability trade hedges to provide cost margins. Conversely, the incumbent spends too much effort explaining and rationalizing what happened on its program of record. Thus, the incumbent is trapped in the “Mea Culpa†of circumstance.

Product Baseline Design. The challenger has the freedom, and is anxious to reflect more customer suggestions and concerns in a more open trade tree optimized design. And, since the incumbent has the benefit of its development experience on its current program, it is unlikely to make enough new and fresh trade choices in selecting its design configuration. It will feature commonality from existing program at the expense of originality driven by the new start requirements. Incumbents are burdened by their last success.

Schedule. The challenger offers the schedule that the customer desires to hear to support key acquisition milestone dates (e.g., first flight, OT&E, Initial Operational Capability, etc.). Additionally, the challenger invests in head start tasks and risk demos to ensure that its schedule is evaluated as credible and executable. The incumbent, with its superior knowledge and incisiveness based on how long it took last time, will credibly claim schedule certainty, which may not fit well in the current acquisition plan schedule. The incumbent is burdened with knowing too much and feels righteous in its realism trap.

Cost. The incumbent’s costs on the program of record are likely known by the challenger, who will adjust them for the product, process, and rate differences (between the incumbent’s program of record and the new program being bid). This enables the challenger to establish the incumbent’s likely cost for the new program. The challenger then sets its cost goal to be less than the incumbent’s likely cost. The challenger then determines its price to win (PTW). The PTW is allocated across the EMD and Production Work Breakdown Structures to determine its Design-to Unit goals and its Buy-to goals for the vendor-provided Bill of Materials. Trades of performance versus cost and risk are used to inform configuration choices driven by cost goals. Meanwhile, the incumbent, with prior program actuals, will claim very credible basis of estimates (BOEs). And with its superior knowledge of the tasks to be accomplished and its incisive awareness of the prior program’s “unknownsâ€, the incumbent is likely to estimate higher costs and associated price than the challenger. Thus, superior knowledge and recent actuals as BOEs set the stage for the too smart to bid competitive trap.

Price. The challenger will use the incumbent’s current unit price as the benchmark and adjust it for differences between the incumbent’s current product configuration and its likely configuration for the new program. Thus, the challenger can rationally “target†the incumbent’s likely price and reflect it in its Price to Win derivation. The incumbent—with its credible, substantiated claims of cost/price reasonableness, realism and completeness—will likely bid higher than the challenger. The incumbent is in the burdened with actuals trap.

Propensity to Take Price Risk. Throughout the pre-RFP effort, the challenger capture team and top management leadership are aligned and committed to win. The challenger will likely bid “just incredible enough†to win.†Meanwhile, the incumbent, for the reasons mentioned above, will likely bid “just credible enough†to lose. The incumbent is often trapped by being “snake bitten†a few too many times, having realized risk driven cost increases on the current program.

Turning the Incumbent Traps into Strengths for Winning

TMI’s next Winning Insights post (May 2017) will address best practices and specific hedges to turn each the incumbent’s traps into strengths. In general, the hedges require the exercise of imperatives by leadership early on to ensure the hedges are not too little, too late.