Deriving “what†and “how to†is a difficult task. It requires some new concepts, incisiveness in thought, and decisiveness in action.  The task can end up in the THTD (too hard to do) category because the “whats” and “how-to’s” may appear threatening to the functional organizations, and often they are generally beyond the capability and authority of the capture team. Thus, a General Management-level leader must be commissioned to lead an experienced cross-functional team to find better, quicker, and cheaper ways to perform. Despite difficulty, our industry is rich with examples of innovation and change in “how to do business†that enables winning.

Franchise Program Competitive Scenario

In Pre-RFP Situation Assessments on “franchise†opportunities, history reveals that at least two competitors can offer acceptable performance, and at least one competitor will view the opportunity as strategic and worth the risk of offering a “gamey†low price. Thus, to ensure winning competitors may need a “play above the rim†strategy (i.e., slam dunk), offering both the best value and lowest Total Evaluated Price.

Practices used to achieve challenging cost goals are described below:

Concept Design – Because product cost is driven by design definition, a paradigm shift in design practices is usually required. During the Acquisition Reform Era (1990s) many companies made the shift from traditional design choices driven primarily by performance to design choices driven by both performance and target costs, i.e., cost became a quasi-independent variable (Cost as an Independent Variable-CAIV).

Metrics – Tracking allocated cost targets as Technical Performance Measures (TPMs) for engineering and Buy-to Goals for Supply Chain (SC) is essential.

Early Price to Win – A PTW (where the competitor’s likely cost/price is the primary consideration) is the imperative for the shift in design practices. Also, PTW precipitates the inevitable “train wreck†associated with the bottom up cost estimate. This provides urgency sooner, with time available, to creatively engineer cost out of the design via CAIV trades of performance versus cost.

Concurrent Engineering (CE) and Integrated Product and Process Development (IPPD) During Concept Design – Early, iterative technical baseline development is critical since 80 percent of design choices driving unit cost are made in the concept phase.  Later design change cost is extreme.

Target Cost Realization in Design and Development Â

Design to Cost (1970s) and Acquisition Reform (1990s) improved realization of target cost goals. Â Now in 2018 and beyond, affordability goals will require:

-Aggressive, achievable cost and performance goals with cost as a constraint.

-Metrics to track and control cost from component level to all-up unit price.

-Customer practices that enable affordability. These include an overarching IPT (User, Acquirer, Requirements Officer, and funding enabler) empowered to make choices on cost versus performance trades, and an acquisition command strong enough to “hold the line†against unnecessary requirements creep.

Product definition is “where you make it†on cost realization. Practices include:

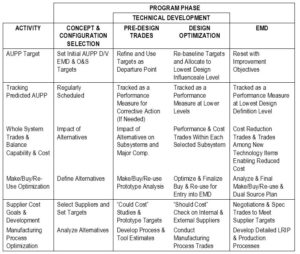

-Cost as a design parameter necessitating Design-to-Cost (DTC) as a pervasive discipline. See Exhibit 1.

-Risk avoidance design policies that include NDI and re-use.

-Architecture to accommodate development changes with minimum impact on cost and schedule. Among these are:

* Open Architecture with design margins.

* Cone of Tolerance provisions. Tolerances are successively more stringent at lower levels (down to modules and further down to components). This accommodates parametric variations that can occur when sub-assemblies are combined and ensures that the next higher-level part meets its requirements and avoids redesign.

-Interface requirements definition. The extent of definition is an important Technical Baseline Maturity metric.

-Commercial practices for subsystems. Highly accelerated life testing and extended margin testing ensure a robust design which minimizes down stream changes.

-Strategic management of Supply Chain.

In the last 40 years, Aerospace & Defense products have shifted from 60-70 percent make to 60-70 percent buy. Thus, cost-driven make/buy decisions and informed, incisive SC management are imperatives. Practices to reduce Bill of Material (BOM) cost include:

-Bundling multiple purchases in to a single purchase to reduce the number of subcontractors (SCXs) and negotiate lower costs for each purchase.

-Selecting a major SCX to buy multiple components and modules, assemble them, and deliver a certified subsystem. Consequently, this practice reduces the number of suppliers and eliminates in-house assembly cost.

-Authorizing multi-year buys of the SCX’s long lead items to reduce SCX cost.

– Offering favorable payment terms for cost reduction.

Additionally, strategic supplier relationships are needed. These practices include strategic teaming with SCX providers of critical mission subsystems. As the quid pro quo for strategic teaming, insist on risk sharing partners who invest up front. Â Past examples:

– Advanced Tactical Fighter (F-22) – As team mates, Lockheed, GD/Fort Worth and Boeing agreed to invest $500 million each in the Fly-Off competition to better ensure the Lockheed team win.

– SBIRS/Hi Satellite – Aerojet and Grumman, sensor suppliers to Lockheed, invested several $100 million of their funds to develop a new sensor.

Oversight of Supply Chain

The critical technology– and risk– is often with major SCXs. Primes and Government program offices often do not have adequate technical visibility and insight into SCX development efforts. Additional and timely interaction by the prime’s program management and subsystem technical project engineers is essential. This often goes against traditional SCX buyer practices; i.e., once the SCX is selected and negotiated, the prime’s engineers are often kept away from the SCX to protect the negotiated baseline and avoid constructive changes. In reality, SCX specs and Statements of Work are not unambiguous and not without errors. Thus, the prime’s project engineers need continued, planned interaction with the SCXs to engineer cost out via spec relief and reduce unnecessary tasks. Also, continuous improvement (upgrades, higher reliability, lower unit cost, etc.) requires engineering effort by both the prime and SCXs throughout TD, EMD and production.

Production Realization of the Production Unit Cost Target    Â

The consummation of the above-mentioned practices, further enabled by Industrial Engineering production efficiency practices (CAD/CAM, DFMA, Open Architecture, Agile, Single Cell, CMI, etc.), is achieving the unit cost target. However, unit cost cannot be realized unless disciplined change management is practiced by both the government and contractor Program Managers and their associated Chief Engineers. They must “hold the line†to minimize changes. Also, to minimize cost, changes must be grouped and implemented as a Block in the next production lot (example: F-16).

In conclusion, “where you make it†on a “gamey†price and a “gooey†schedule lies with: (1)  product definition with user, developer and contractor collaborating on trades to best balance capability, cost, and risk; and (2) contractor program and technical management wherein the management team holds reserves in performance, schedule, and cost as the “currency†to trade and unlink cost to keep it as independent as possible during design and development.

TMI’s next Winning Insights series will address strategy choices, investments, and initiatives in pre-award phases (Shaping the Game, Teaming, Technical Solution, Pricing, and The End Game) that were the “game breakers.â€

Exhibit 1: CONTINUOUS DESIGN-TO-COST ACTIVITIES

Managing Cost as an Independent Variable